Lauren Barra, KF16 Kenya/Tanzania

Last month I had the privilege of attending the African Microfinance Pricing Transparency Leadership Forum in Nairobi. Hosted by MicroFinance Transparency, the conference gathered policymakers and regulators to exchange ideas about client protection and pricing disclosure in microfinance. Attendees included representatives from over 20 nations in East, West and Southern Africa.

What does “transparency” entail? Transparency represents an organization’s commitment to communicate price from the client’s perspective. It is a means to an end – we cannot build a healthy microfinance industry without transparency. As we’ve seen with SKS in India, the industry risks immediate backlash if consumers and investors no longer trust microfinance institutions. Clever marketing and hidden interest rates or fees make it difficult for clients to make educated choices. Without accurate data, regulators are essentially navigating in the dark, forced to make decisions without context. Transparency is the strongest tool available for improving these market imperfections.

Microfinance is rapidly expanding and MFIs often face pressures to dilute their social mission in pursuit of competitiveness. The danger lies in that it’s easier to hide prices than face tough choices about efficiency. Over the course of three days, conference participants debated big questions that will determine the future of the Africa’s microfinance industry. For example:

- Who is responsible for promoting transparency? Government regulators? Donors and investors?

- When, if ever, is it appropriate to cap profits and interest rates?

- How do we prevent over-indebtedness?

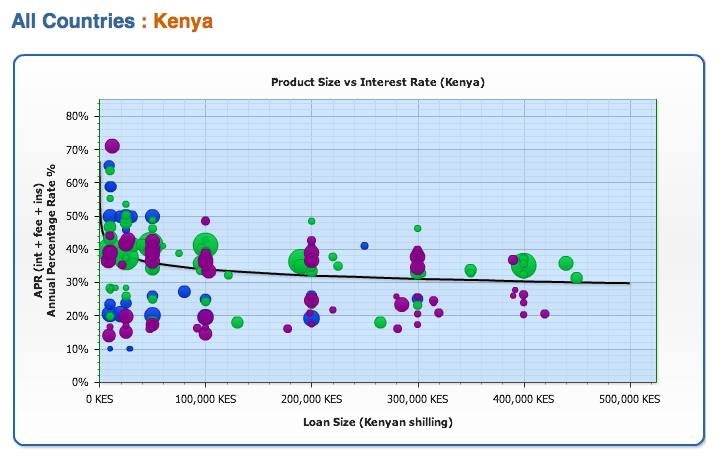

As the group wrestled with these questions, we walked through examples of microfinance rates and regulations around the world. For example, Kenya has no transparency regulation and as a result there’s tremendous variability in their pricing (see graph below). Kenya also has two separate regulatory agencies for deposit-taking MFIs – the Central Bank of Kenya and SACCO Societies Regulatory Authority (SASRA). This system presents challenges with aligning policies and enforcements, unfortunately resulting in deceitful institutions slipping through the cracks.

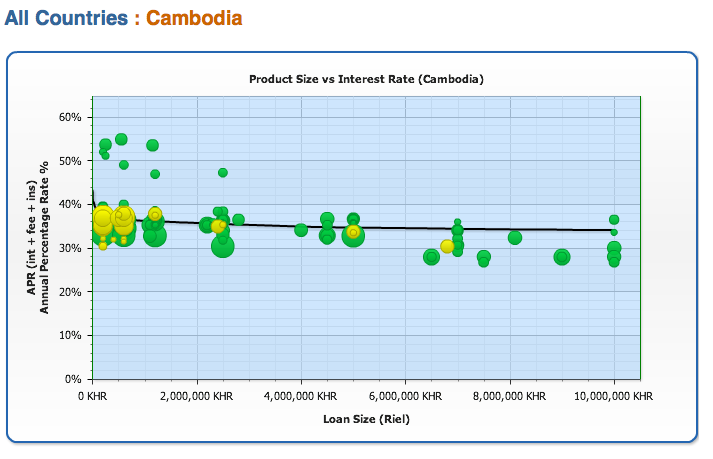

The Philippines’ Truth in Lending Act requires the conspicuous display of fees, interest rates, and the total cost of credit at branch offices. In Bosnia, all MFIs must use the same repayment schedule template – providing borrowers with a simple apples-to-apples comparison between microfinance institutions and products. Cambodia made the flat interest rate, a deceptively simple calculation, illegal in 2001. According to Cambodian Microfinance Association, effective interest rates have declined from 10% to 3–3.5% per month, due in part to the change in calculation method from flat rate to declining balance. The results are also evident in the interest rate curve seen below, with prices moving predictably and consistently in accordance with loan size.

Implementing similar client protection principles in Africa sparked a heated debate among participants. Is it better for governments to define one formula for calculating interest rates? Or publish reports on actual prices and let market forces decide? Although their views varied greatly, these policymakers and consumer advocates could all agree on one point. Regulators should not be fully responsible for promoting transparency – donors and investors must also play an active role.

—

With $255MM disbursed to over 600,000 borrowers, Kiva is one of the largest microfinance donors in the world. So what should Kiva’s role be in promoting a healthy, transparent microfinance industry? Two questions arise:

- Does Kiva have a responsibility to promote microfinance transparency?

- What must Kiva do to meet this responsibility?

I believe the answer to the first question is a definitive “yes.” Kiva already acknowledges some measure of responsibility for accurate reporting from Field Partners. Client Waivers must be signed by each Kiva borrower and presented during the annual Borrower Verification. As I discussed in an earlier post, Kiva assigns “transparency” as a key criterion in their evaluation of Field Partner risk ratings. Partners which don’t follow Kiva’s guidelines face rating downgrades and in the case of fraud, are completely cut off from funds.

The second question is much trickier to answer. Obviously fraudulent and corrupt institutions should be banned from Kiva’s platform. But what about institutions that charge higher than average interest rates? Or MFIs that are undergoing a noticeable mission drift? Kiva is now taking steps to identify these problem areas at its Field Partners. In addition to a Social Performance Audit, certain Kiva Fellows will perform a pilot survey of Client Protection Principles (CPP). Developed by the SMART Campaign, CPP are a set of standards that clients should expect to receive when doing business with a microfinance institution. They ensure that clients’ needs are being addressed throughout the loan process and that an MFI is “doing no harm.”

While this effort is commendable the real question is – what will Kiva do with this information? In theory, the CPP will “eventually enhance the Borrower Verification with additional elements to better understand the relationship between the MFI and their client and to highlight areas of improvement in their commitment to client protection.” But is “highlighting areas of improvement” really enough? Kiva’s reputation and financial standing puts it in a unique position to influence microfinance transparency and client protection. When Kiva talks, MFIs, investors and policy-makers listen. Shouldn’t Kiva use this position to make swift, decisive changes at its Field Partners in order to protect microfinance borrowers?

I’m not advocating that Kiva should be a watchdog agency for nearly 150 MFIs in 60 countries. But I do believe the title of “game-changer” compels Kiva to a higher standard of responsibility. This means clearly defined standards for client protection and cost of credit, consistent evaluation of Field Partners, and real consequences for organizations that fall short of these expectations. The potential for decreased fundraising limits, rating downgrades or even a “CPP Certified” label would all incentivize Field Partners to implement CPP standards as swiftly as possible.

With great power comes great responsibility and in this case, Kiva is more than capable of rising to the occasion.

Lauren Barra is serving as a Kiva Fellow with Yehu Microfinance Trust in Mombasa, Kenya and Tujijenge Tanzania in Dar es Salaam.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

NFS Series: Education Services Part 2: Education & Microfinance →NEXT ARTICLE

Red and Black to Pink, Peace and Love: The Reign of Daniel →