This is a guest post contributed by Kiva Fellow Esther Honig, who is stationed with our partner Fondo Esperanza in Chile.

In a rural town outside the southern city of Curico, Chile, I’m sitting at a small fold-out table with a 60-year-old Kiva borrower. I’ve just taken photos of her posing proudly inside her business, a small cinder block restaurant that she’s owned for the past 10 years. She’s flattered to have her picture taken and to know that thousands will see her on the internet. But, in order for Kiva to use any of these images, she must sign a release form.

“I can’t read without my glasses,” she says, adjusting the piece of paper in front of her face.

The small black-and-white print explains in simple Spanish that, with her permission, this image will be posted to the Kiva.org website.

I retrieve her glasses from behind the kitchen counter, but once she has them on, her face holds the same confused expression.

I explain to her that if she agrees to these terms, she’ll need to include her printed name, signature, date and address. She gives me a nervous look and says, “But dear, my handwriting is very bad.”

At first I’m puzzled. Why is this borrower suddenly so reluctant to fill out the waiver?

Then I realize it -- possibly for the first time in my life, I’m meeting with an adult who can’t read or write.

As of 2010, UNESCO estimates that there are 775 million illiterate adults in the world. Over two-thirds of this population is found in only eight countries: Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan. In these regions, south and west Asia, the Arab states and Sub-Saharan Africa -- where literacy rates are lowest -- Kiva works with 102 field partners.

In addition to personal hardship, illiteracy creates major obstacles for economic development. If someone can’t read or write, they also can’t balance a checkbook, read a bank statement or make an informed investment.

So how have Kiva’s partners adapted to work with these borrowers -- including many who can’t read required documents or sign their own names?

Here are some great examples:

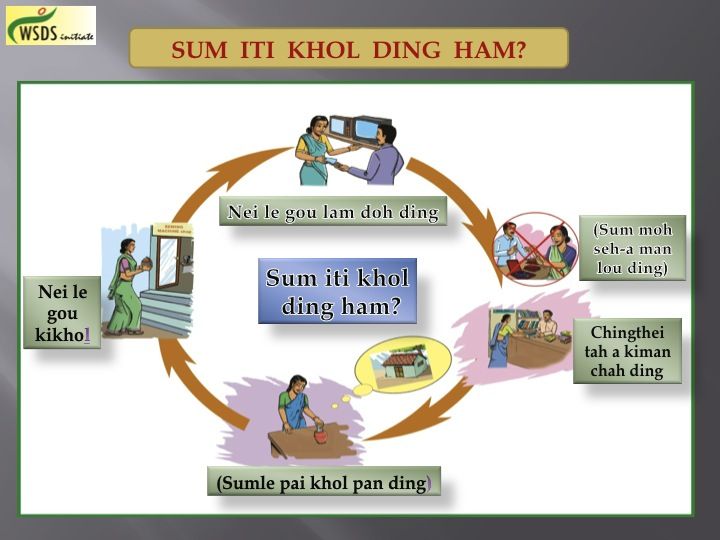

Microfinance institution WSDS-Initiate is located in the northeastern state of Manipur, India -- a country with one of the largest illiterate adult populations in the world. So the staff at WSDS is familiar with the challenges of serving a largely illiterate clientele. That’s why they’ve developed a three-day literacy-training course aimed at assuring the success of each borrower, regardless of their level of education.

This course begins with the most basic of skills: teaching borrowers to sign their name and to create a budget.

Instructors take the time to verbally explain each concept and use didactic materials that are highly visual so participants can follow along without having to read the text.

Concepts get more advanced as borrowers learn about what makes a good investment and how to maintain a savings account.

In Senegal -- where 50% of the adult population is illiterate (Worldbank) -- Kiva field partner Caurie has developed a similar strategy to assure the success of its borrowers.

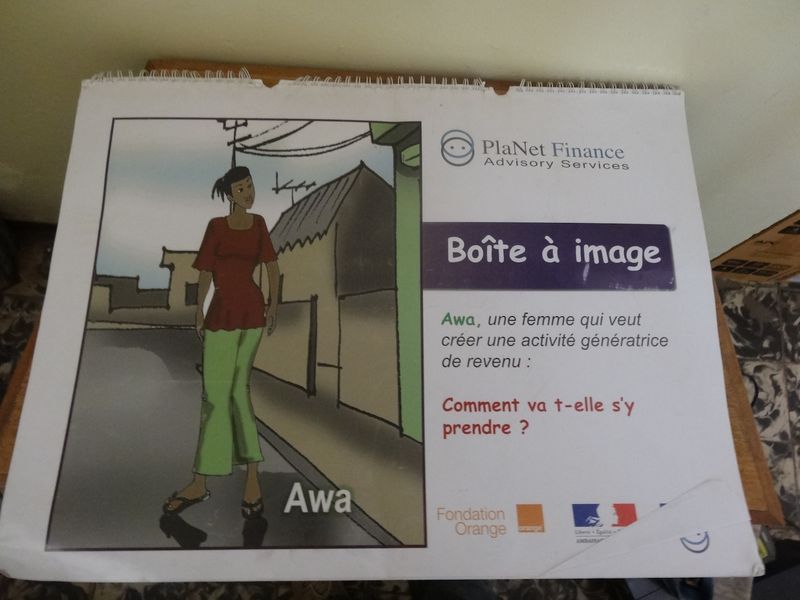

At Caurie, first-time borrowers also undergo a three-day training course where visual materials -- based on real-life scenarios -- teach borrowers the basic skills necessary for running an effective business.

“Awa, a woman who wants to develop a lucrative activity. How will she do it?”

“I know my monthly costs. I have an idea about the number of breads I can sell… I know how much the flour costs, the delivery, the rental, the staff salaries... So I know the amount of money I need to start: I need 1 530 000 to launch my business, knowing that I already saved 250 000…” How does she evaluate her start-up capital?

As is true of many microfinance institutions, borrowers at Caurie have the option of signing their loan documents with a fingerprint if they are unable to sign their names.

In Guatemala -- a country with one of the lowest literacy rates in Central America and where over 20 indigenous languages are spoken -- MFI Friendship Bridge accommodates borrowers who have 2.3 years of formal education on average, and are not likely to speak Spanish.

Friendship Bridge has developed non-formal education lessons that are interactive and highly visual to engage these borrowers. Furthermore, all loan officers are required to speak the same Mayan language as their clients.

Pictured above: Borrowers learn about family planning. All of the members are challenged to stand together on a newspaper placed on the ground. After each round, the paper is torn into a smaller piece making it more difficult for the group to maintain its balance. The activity is meant to illustrate that it is hard to sustain a large group on small resources. In the same way, effective financial and family planning will help them better support their families.

In Mexico, Kiva field partner IluMexico, a solar energy social enterprise, faces challenges similar to those in Guatemala.

IluMexico provides rooftop solar systems to households in the country’s rural areas where people lack basic infrastructure like electricity and running water.

The majority of clients are indigenous Mexicans who, on average, have received only 4.6 years of formal education and have an illiteracy rate of 27%. Additionally, it’s likely their primary language is one of the country’s 68 indigenous languages and not Spanish.

To overcome these communication challenges, IluMexico has incorporated a universal design into their solar-powered systems.

The controls are simple and intuitive, labeled with colors and symbols that are easy to understand so that users don't need to be able to read to operate them.

Back in Curico, Chile, local MFI Fondo Esperanza has an even simpler solution. In a country with an illiteracy rate of only 1%, loan officers don’t face the same hurdles as those in India or Guatemala. However, illiteracy can still be an issue, mostly among elderly borrowers like the restaurant owner who couldn’t read the Kiva waiver. They are also most likely to be too embarrassed to admit to their inability.

In these cases, loan officers are discreet and take the extra time to read loan documents out loud and double check to make sure clients understand.

Following their example, I read the client waiver to the proud restaurant owner and made sure she understood. She signed her name, and I helped her write the date and print her address.

In this moment, I’m reminded that accessible credit is only a fraction of the services Kiva field partners provide for their borrowers. It’s worth knowing that behind each Kiva loan there is a considerable amount of consideration paid to the particular needs of each borrower.

Whether it means hours of lesson planning, years developing the best curriculum, or simply designing a more straightforward light switch, Kiva insists on partnering with those committed to providing a more comprehensive service, because in the end what’s best for the borrower it what’s best for Kiva.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

A Less Self-Conscious Carnaval in Asuncion, Paraguay? →NEXT ARTICLE

Volunteer Spotlight: Kyla Evans, globetrotter, closes in on 5,000 loans edited! →